Introduction

What is Anabaptism? Why does Anabaptism matter? This article is an attempt to briefly answer those two questions.

One of the most defining moments in church history occurred in 1523 in Zürich, Switzerland. The religious atmosphere in Western Europe throughout the medieval period was predominantly Roman Catholic, but change was in the air. In 1517, the German theologian Martin Luther began to officially challenge the Catholic system. His ideas started to spread throughout Europe.

In Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli had been a Roman Catholic priest until his study of the Bible led him to break with that tradition. It was in the early 1520s that Zwingli, an excellent Bible scholar, was teaching a group of his students to study the Scriptures. That included introducing them to the Greek New Testament. Zwingli was unknowingly watering the seed that would become the Anabaptist movement.

As it turned out, those students took the Bible study more seriously than their teacher had anticipated. Zwingli’s students included Conrad Grebel, Felix Manz, and Simon Stumpf. They expected that an understanding of the Scriptures would produce transformed lives.

These young men began to challenge the prevailing religious system. One of the changes they desired to see related to the need for believers’ baptism. Although infant baptism was the practice of the Catholic Church, Zwingli’s students believed that the Bible taught adult baptism upon confession of faith. The city council called for meetings where that matter could be discussed. The civil authorities wanted to control the changes that would be made. At one of those meetings, Zwingli, instead of standing with his students, deferred to the city council.

When Zwingli was asked how to proceed with decisions about following Scripture, he said, “My lords will decide.” His students were shocked. How could their respected Bible teacher now defer to and allow the city council to make decisions about biblical teaching? When Zwingli said, “My lords will decide,” Simon Stumpf famously responded, “Master Ulrich, the Spirit of God has already decided!”

These young men were committed to following the Spirit of God in the face of whatever the authorities would do to them. Zwingli, their teacher, had deserted them at a time when they desperately needed him. What would they do? Would they follow their teacher? Would they follow the authorities? Who or what was the authority? Who or what should be the authority?[^1]

A basic conviction of the Anabaptist movement is that the only safe authority is the Bible, as studied under the direction of the Holy Spirit. This was the conviction of Zwingli’s students in 1523. This commitment was foundational for the beginning of the Anabaptist movement. But how did the church get to the point where the civil government was given the authority to make theological decisions for the church? Does that sound like the church we read about in the New Testament?

The Early Church

The birth of the church is recorded in Acts 2. Jews from around the Mediterranean world had come to Jerusalem to observe the Feast of Pentecost. The Holy Spirit descended on Jesus’ disciples, and the church age was officially inaugurated. As the book of Acts describes, the Christian community assembled frequently for instruction, prayer, worship, and meals. That raises another question: what is the church? The historian John D. Roth defines the church as “a gathering of committed believers drawn together by a common set of convictions and determined to live out their vision of an alternative way of life.”[^2]

Roth goes on to note six distinctive elements of the early Christian community, especially as seen in the book of Acts.

- Voluntary membership (the members of the church were united by their conscious decision to follow Jesus).

- Sharing of possessions (the Christian community took seriously their responsibility to provide for the physical needs of the members).

- Mutual accountability (the Christian community took seriously their responsibility to provide for the spiritual well-being of the members).

- Commitment to nonviolence (the Christian community refused to use physical force).

- A distinctive culture (the Christian community was distinct from the world around them).

- Mission-mindedness (the Christian community was active in calling others to join them).[^3]

Changes in the Church

As movements develop, they will experience challenges. At some point, there must be a shift from movement to structure, and that is what the early church experienced. One example of that structure was the statements of faith (creeds) that were written to clarify significant theological issues. While a progression from movement to structure is necessary, there are also some dangers associated with it. “Structures tend to become ends in themselves … Doctrines … can become tools of power in the hands of leaders interested only in maintaining their own authority. In the process, the calling of Christ to faithful discipleship can be forgotten.”[^4]

As history unfolded, that is what happened. Jesus’ instructions to His followers to live a life of discipleship were eventually muted as the essence of the church was redefined. The fourth century of Christian history has been described this way: “It was a remarkable century. What began as the ‘Era of the Martyrs’ under Diocletian ended with the emergence of Christianity as the religion within the empire.”[^5] In 312, Constantine became a Roman emperor (he was a co-emperor along with Licinius). Significantly, Constantine professed a belief in Christianity. Constantine and Licinius granted freedom of worship to Christians. Eventually, Constantine moved from tolerating Christianity to promoting Christianity.[^6]

While his predecessors had sought to establish empire-wide stability by suppressing Christianity, Constantine took a different approach: he sought “to exploit its potential for unity.”[^7] That led, for example, to his involvement with the Council of Nicaea (325). A Roman Emperor presided over an assembly of church leaders!

“Under Constantine and his successors, Christianity went from the persecuted religion of a minority to the state religion of the Roman Empire.”[^8] That alignment of church and state has persisted throughout history, and it has arguably had more of an impact on the character of the church than on the character of the state. In the medieval world (from the fifth to the fifteenth centuries), the Roman Catholic Church dominated Western Europe. Every child born in the so-called “Holy Roman Empire” was baptized as an infant and so became a lifelong church member.[^9]

The Birth of Anabaptism

Returning to Switzerland, in a Zürich city council meeting in January 1525, Zwingli’s students were denounced. The students were zealous for reform, and their convictions had pushed them beyond Zwingli. After Zwingli was declared the victor in the debate, the denounced students had three options: “The little group could conform, leave Zürich, or face imprisonment.”[^10] Which path would you have chosen?

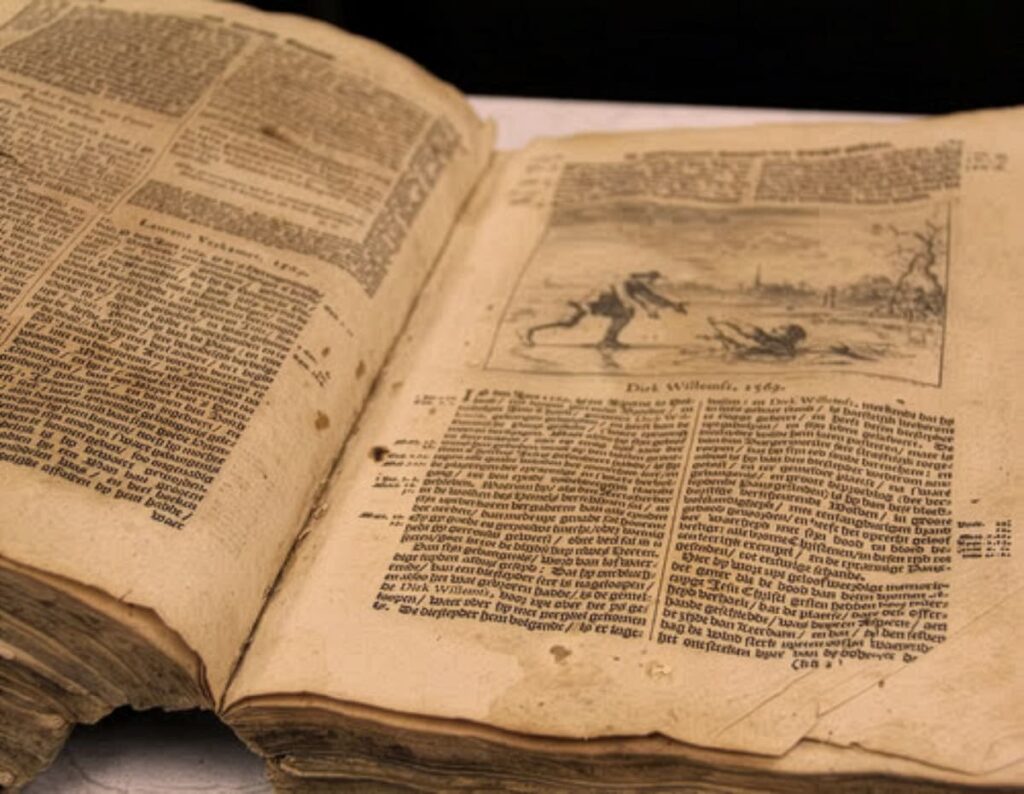

On January 21, 1525, a group of young people decided to reject the validity of their baptism as infants. At the Manz household in Zürich, just down the street from Zwingli’s Grossmünster (“great cathedral”), George Blaurock “stood up and asked Conrad Grebel, for the sake of God’s will, to baptize him with a true Christian baptism on his own faith and confession.”[^11] After Blaurock was baptized, he went on to baptize the rest of the group, all of whom committed themselves to live as faithful disciples of Jesus. It has been said that “This was clearly the most revolutionary act of the Reformation … Here, for the first time in the course of the Reformation, a group of Christians dared to form a church after what was conceived to be the New Testament pattern.”[^12]

The Swiss Brethren, as they came to be called, continued to perform baptism upon the confession of the recipient’s faith. They also celebrated the Lord’s Supper in their congregations. These practices were viewed as acts of anarchy because the Swiss Brethren were operating “outside the structure of Zürich’s established church order.”[^13]

Furthermore, these believers refused to allow their children to be baptized as infants in the state church. Strikingly, on January 14, 1525 (one week before the first believers’ baptisms), Conrad Grebel wrote this in a letter to his brother-in-law Vadian: “My wife was delivered yesterday, that is Friday, a week ago. The child is a daughter and is named Rachel; it has not yet been baptized and watered in the Romish water bath.”[^14]

The term “Anabaptist” technically means “re-baptizer.” That title makes some sense because the first Anabaptists had all been baptized as infants. However, they also rejected the validity of infant baptism and so regarded their adult baptism as their first true baptism.[^15] Hence, the early Anabaptists preferred to refer to themselves as “Brethren” or as “Baptism-minded.” Nevertheless, “…the Anabaptist name stuck. Despite its negative overtones in the sixteenth century, Anabaptist has since become an accepted term for Reformation groups who practiced believers (rather than infant) baptism.”[^16]

The meeting on January 21, 1525, was the beginning of a movement. The worldwide Anabaptist church (which includes Amish, Mennonites, Hutterites, Brethren, and related churches) has grown to around 2.1 million members in over 80 countries around the world.[^17]

Major Anabaptist Emphases

After this explanation of Anabaptist origins, the focus should shift to responding to the question, “Why does Anabaptism matter?” There is a little-known historical episode that captures an important element of the Anabaptist worldview.[^18]

In the 1500s, Reformed theologians were expected to debate with the Swiss Brethren. It was hoped that those debates would convince the Swiss Brethren to abandon their distinct theological emphases. Those theologians arranged for formal debates on subjects such as the nature of God or the doctrine of the Trinity. Being university-trained, their focus was on technical points of historic Christian theology. In contrast, the Swiss Brethren were more interested in practical issues relating to the Christian life. They pursued a simple understanding of Scripture that their critics viewed as being simplistic.

It was in 1571 that Reformed theologians were pushing the Swiss Brethren minister Hans Btichel to respond to the question of whether or not the Old Testament patriarchs were saved. This was his response: “The Lord knows best when those of old entered heaven. I am not commanded to dispute what took place one or two thousand years ago. I am commanded to do right, and this is my lifelong aim. The secrets which God reserved for himself, I wish to entrust to God.”

The exasperated leader of the Reformed delegation is said to have responded by saying, “Then why debate? You could have just sent the Bible and said ‘This is our understanding!’ ”

This historical account is significant because of the testimony, from the mouth of an opponent, that the early Anabaptists understood the Bible simply and yet also seriously.

It should be noted that the Anabaptists shared with other Christian groups a belief in the historic theological statements of the church. To understand why Anabaptism matters, it is helpful to consider some of the theological points that Anabaptism emphasizes. This discussion is not intended to convey that no other Christian group holds to these positions. Rather, the focus here is on highlighting four important points of emphasis in Anabaptist theology and practice.

First, the early Anabaptists held to a position that could be called “simple, literal biblicism.”[^19] From that perspective, the Bible is the primary source of spiritual truth and ethics. In particular, the Anabaptists took the words of Jesus seriously. Dean Taylor captures this sentiment with his question, “What if Jesus really meant every word that he said?”[^20] As a bumper sticker states, “When Jesus said ‘Love your enemies,’ I think he probably meant don’t kill them.”[^21] In the words of Grebel himself, “I believe in the word of God without a complicated interpretation, and out of this I speak.”[^22]

Second, the early Anabaptists held to the centrality of Jesus. While it is likely that many Christians would claim that Jesus is at the heart of their belief system, there is also significant disagreement among Christians about how exactly the centrality of Jesus is to be understood.[^23] Many Christians rightly emphasize the significance of Jesus’ death and resurrection. However, that sometimes leads to a minimization of Jesus’s life and teachings. In the Anabaptist tradition, the centrality of Jesus has been promoted by an emphasis on following His life and teachings.[^24]

To the early Anabaptists, “Jesus’ life and teachings were of extreme importance. They were not, however, separated from His death and resurrection!”[^25]

Third, the early Anabaptists emphasized what Paul Lederach calls “the wholeness of salvation.”[^26] This was a logical outgrowth of their commitment to being disciples of Jesus, which meant that they were to follow his teachings in their daily lives. In this approach, salvation is understood to involve the whole person. That means that salvation must be about more than giving mere mental assent to a set of theological propositions.[^27] While the verbal acknowledgement of Jesus as Lord is vital, that acknowledgement must also be evidenced in a person’s actions.

The Anabaptist understanding of the wholeness of salvation includes acknowledging that the Bible is about much more than individual salvation. As Lederach puts it, “The question, ‘Are you saved?’ is not enough. ‘Do you know Jesus and are you following him as part of his church?’ is a better question.”[^28] An essential aspect of following Jesus is being a member of a community of faith. Faith must find expression in life. The work of the Holy Spirit is made evident through transformed lives. If someone is truly a believer, other people will notice. When a traveling preacher asked a Mennonite farmer if he was saved, the farmer replied, “I could tell you anything you want to hear. If you really want to know if I am a Christian, you will need to ask my neighbors.”[^29]

Fourth, the early Anabaptists were unique in sixteenth-century Europe because they practiced believers’ baptism. Water baptism was understood to symbolize “…a transformation of the heart; a commitment to a new life of discipleship to Jesus; and membership in a new community of believers.”[^30] In contrast, the infant baptism tradition does not connect baptism with repentance.[^31] Believers’ baptism could be compared to a wedding. Similar to a wedding, in baptism, a public commitment is made before God and witnesses. Additionally, just as there is more to a marriage than a wedding, so is there more to the Christian life than baptism. As important as baptism is, the Christian life must be lived daily.[^32]

Conclusion

These four points are significant components of New Testament Christianity, and a strength of the Anabaptist movement is its commitment to these teachings. Who will be a modern-day Simon Stumpf? Who is willing to stand firmly on Scripture? As the authority of Scripture is under increasing attack, Christians must be willing to proclaim, “The Spirit of God has already decided!”[^33] In the words of Harold S. Bender, “If we abandon our confidence in the Bible, the Mennonite church is lost; we will ultimately disappear in the stream of history.”[^34] God’s Word will last forever, and it is that to which we must cling.

Bibliography:

Bender, Harold S. Biblical Revelation and Inspiration. Scottdale, PA: Mennonite Publishing House, 1959.

Brethren Press. “When Jesus Said” – Bumper Sticker. https://www.brethrenpress.com/product_p/wjsbumper2020.htm

Dowley, Tim. Atlas of the European Reformations. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2015.

Estep, William R. The Anabaptist Story: An Introduction to Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism. Third edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1996.

Hannah, John D. A Pivotal Era, in Tabletalk Magazine, August 2004: A Defining Era: The History of the Church in the Fourth Century. Lake Mary, FL: Ligonier Ministries, 2004.

Lederach, Paul M. A Third Way. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 1980.

Liechty, Daniel. “Introduction.” In Early Anabaptist Spirituality: Selected Writings, edited by Daniel Liechty and Bernard McGinn. The Classics of Western Spirituality. New York; Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1994. Mennonite World Conference. Membership, Map and Statistics. https://mwc-cmm.org/en/membership-map-and-statistics/, 2025.

Needham, Nick. 2000 Years of Christ’s Power: Renaissance and Reformation. Revised edition. Volume 3. Scotland, U.K.: Christian Focus, 2016.

Noll, Mark A. Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity. Third edition. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2012.

Miller, David I. (compiler). Anabaptist Quotations. A document prepared for the February 1989 Ministers’ Fellowship meeting of Conservative Mennonite Conference.

Reed, Frank. The Spirit of God Decides. Biblical Brethren Fellowship, https://biblicalbrethrenfellowship.wordpress.com/2012/08/05/the-spirit-of-goddecides/

Roth, John D. Beliefs: Mennonite Faith and Practice. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 2005.

__________. Stories: How Mennonites Came to Be. Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 2006.

Taylor, Dean. “The Essence of Anabaptism.” Anabaptist Perspectives. January 3, 2018. https://anabaptistperspectives.org/episodes/the-essence-of-anabaptism/

__________. “What If Jesus Meant Every Word He Said?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7y0mqqJwFg.

Vos, Howard Frederic. Exploring Church History. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1996.